STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Controversy over Martin Luther King Memorial includes truncated quotation

- Maya Angelou charged that paraphrase makes King seem "arrogant"

- Most people think only of "I have a dream," but King far more complex, challenging

- King's words and humanity still speak to us today

(CNN) -- Of course a memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. was going to be controversial.

The man himself was controversial, notes LaSalle University sociology professor Charles Gallagher. King -- bound up with issues of racial and economic inequality that spotlight America's worst sins -- is a "Rorschach test," Gallagher says, that people see in King what they want to see.

Still, few of the organizers of the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial in Washington may have expected that every little detail would be so scrutinized, criticism that has continued right up to the first Martin Luther King Jr. Day since it opened last fall.

Late Friday, the Department of Interior -- which has jurisdiction over the memorial -- announced a quotation in the memorial's King sculpture would be changed. This action followed months of complaints about the language of the quotation, which had been paraphrased from a passage in a King sermon.

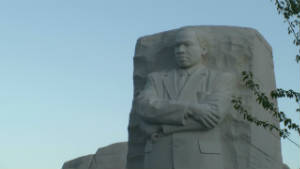

The memorial itself consists of the 30-foot sculpture of King, called the "Stone of Hope," in which the civil rights leader emerges from a portion of a granite slab. Some yards away is a mountain of granite; together, the pieces give life to King's words from his 1963 March on Washington address: "Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope." Nearby stands a low wall engraved with 14 King quotations on subjects including love, justice and hope.

The disputes started not long after the memorial was officially approved about 15 years ago.

Initially, there was disagreement over the location; several months went by before a Tidal Basin site was selected. There were criticisms about the choice of sculptor Lei Yixin, a Chinese national; the use of Chinese granite; King's pose, which has been called "confrontational"; and even its scale, which has been likened to Soviet-style monumentalism.

The capper may have come last fall, when the carving was unveiled. One side of the Stone of Hope features a quotation drawn from "The Drum Major Instinct," a 1968 King sermon: "I was a drum major for justice, peace and righteousness."

The words, critics have noted, were edited from a longer quotation in which King stressed the conditional: "If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice," the passage begins.

Poet Maya Angelou, a member of the MLK Memorial's Council of Historians, told The Washington Post that the inscription made King look like "an arrogant twit."

"He would never have said that of himself. He said 'you' might say it," she said.

Ed Jackson Jr., the memorial's executive architect, responded that the quote was paraphrased for space reasons and that the National Commission for Fine Arts, which oversees the memorial, "didn't have a problem with it."

Friday, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar gave the National Park Service 30 days to consult with the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, members of the King family and others to decide on a more accurate version of the quote, a department official told CNN.

Historians have mixed feelings about the quotation. One said he was troubled; another called the dispute "a tempest in a teapot."

Indeed, King isn't the first luminary to have a quotation misused. The Jefferson Memorial, across the Tidal Basin "juxtaposes fragments (of Jefferson's writings) ... to create the impression that he was very nearly an abolitionist," writes historian James Loewen, author of "Lies My Teacher Told Me."

But perhaps the primary criticism leveled at the memorial is one that can be aimed at any creation of this type: that it freezes its subject in stone. Sculptor Daniel Chester French's Abraham Lincoln, across the Mall, is a gorgeous work, but he is now brooding for all eternity. Franklin D. Roosevelt, nearby, was originally represented by a statue apparently based on the weary president at Yalta; a second FDR, showing him in a wheelchair, was added after protests.

Martin Luther King was a complex man, but how much does the memorial capture that complexity? For that matter, how much does any consideration of the civil rights leader?

"King has been sanitized by a generation, if not two generations, of elementary school kids being raised on Martin Luther King as a dreamer," said University of Hartford history professor Warren Goldstein. "The sanitizing of King's reputation that's happened as the result of the endless repetitions of 'I have a dream' has meant that most people know relatively little about King."

Truth and power

Much of King's fame rests on saying truth to power. He preached about inequality; he marched to change laws and minds. When he was assassinated, he was planning a massive Washington protest for his "Poor People's Campaign" that, if organizers thought it necessary, would have shut down the city. An "Occupy Washington," if you like.

For his troubles, he was insulted, beaten, jailed and had his house bombed.

"King was one of the most admired and arguably the most hated man in America, even at the time of his death," Goldstein said.

And King was, pardon the phrase, an equal-opportunity challenger. He exhorted the dominant white culture to live up to the Founders' promises, but he also confronted African-Americans to improve their place in life.

The TV series "The Boondocks," based on the Aaron McGruder comic strip about two angry black kids in suburbia, offered a sense of the King who struggled to be heard. In perhaps its most famous episode, the Peabody-winning "Return of the King," King didn't die in 1968 but lay in a coma for more than three decades. Upon viewing 21st-century black culture, he berates an audience of African-Americans and storms off.

Even King's most famous speech, the stemwinder given at the 1963 March on Washington, wasn't all about "I have a dream." That portion, which closed the address, was an improvised conclusion to a speech that began with a call for economic and social justice.

"Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked 'insufficient funds,' " he says early in the speech.

Those issues of poverty and equality still matter today, says Jason Purnell, a public health professor at St. Louis' Washington University.

"The problems of the poor and the problems of the African-American community are American problems," said Purnell, who co-wrote an opinion piece about the subject for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. "If you have an entire segment of the population that's in poor health or doesn't have access to educational resources, that's a drag on the economic output of the United States, and it's abandoning a resource that your country has."

The post-King generation

Part of the problem, says Gallagher, ironically lies in the progress of the African-American community since the heyday of the civil rights movement. The black middle class has grown, black culture is more mainstream, and the United States even has a black (or, as some would emphasize, biracial) president now.

"A lot of white America, if you look at the survey data, have come to believe that the goals of the civil rights movement have been achieved," he said.

Most people know relatively little about King.

Warren Goldstein, University of Hartford history professor

Warren Goldstein, University of Hartford history professor

And yet it wasn't so long ago that even the prospect of a Martin Luther King Day engendered protests. The first bill to create a federal holiday failed in 1979; it took corporate activism and a "Happy Birthday" song from Stevie Wonder to raise its public profile. It was signed into law in 1983 and first observed in 1986 -- though not every state went along with the idea. A late-'80s move by Arizona to rescind the holiday cost the state the 1993 Super Bowl.

But now that the third Monday in January is an official day off, it's easy to overlook the man the day is named for. Some communities and schools stress public service to honor King and his ideals, but -- like so many other American holidays -- Martin Luther King Jr. Day has become an excuse for appliance sales, social gatherings and sleeping in.

"I think you get a real mixed sort of response to King Day more than any of the holidays I know of," said Houston Roberson, a civil rights historian and professor at Tennessee's University of the South. "My sense is, in the places I've lived, the efforts (at service) tend to be led by older people. My concern is that it might not be translating to the next generation."

Indeed, because spring semester at many colleges doesn't begin until after King Day, students are usually just arriving for classes around the holiday.

Roberson also finds that his students have a "pretty one-dimensional" understanding of the man, believing that King was raised poor (he was actually from a middle-class Atlanta family) and that he deserved the lion's share of the credit for the civil rights movement, as opposed to being one of many leaders.

"I think he would want my students to know that more people than just him and a few other preachers were involved in the movement. So what I try to do in my classes is to complicate their idea of who he is, both as a man and as a leader," Roberson said.

And, as scores of biographers have revealed, King was eminently human: emotional, guilt-ridden, flawed. Goldstein, who teaches a freshman seminar on King, says his students -- black and white -- are surprised to find out about King's early life, which included flashy clothes and a ladies' man reputation. After reading one letter in which a youthful King boasted about his skills as a seducer, one student expressed shock.

"I think he's kind of a tool," she told the class.

The inspirational King

Certainly, King's hopes are by no means fulfilled.

Our political invective -- some aimed at the have-nots, sometimes racially tinged -- is harsher than ever. During the Republican primary campaign, both Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum were called out for comments directed at African-Americans. (Santorum, who had said, "I would not make black people's lives better by giving them other people's money," later denied that he had used the word "black" but said he had gotten "tongue-tied" and said "blah.")

And we live in an atomized culture, one in which it's easier than ever to tune out the issues of the world, even as we're more connected than ever. It's led to more shouting, more self-promotion, more ego.

Which is why King still matters. He still has much to teach us.

Would King have minded a Chinese sculptor? No, believes Roberson; King's beliefs about people were not based on race. Would King have disliked his forthright pose? It may not be reflective of the whole man -- few statues are -- but it certainly stands for the challenge he offered America.

And his memory still has meaning.

Kevin Liles, a businessman and former record label executive, thinks of King in his many philanthropic activities. Andrew Rojecki, a communications professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago, finds that his students -- born a quarter-century after King's death -- respond to King's name with respect and admiration, which left Rojecki "really heartened and surprised."

Attendance at the MLK Memorial has been strong since it opened in September. The National Park Service, which monitors the Mall attractions, says that 382,000 visited the first month, more than came to the FDR Memorial. In October, the most recent month for which statistics are available, the MLK Memorial drew 448,000 people, almost 50,000 more than the Lincoln Memorial.

So committees may bicker. Politicians may argue. Citizens may wonder what all the fuss is about.

Perhaps, then, it's best to let King have the last word. "The Drum Major Instinct," after all, was played at his funeral, two months after he delivered it at Atlanta's Ebenezer Baptist Church on February 4, 1968.

Out of context or not, his speech still reverberates.

In the sermon, King -- drawing on the biblical story of Jesus, James and John (Mark 10:35-45) -- talked about the instinct "to be out front, a desire to lead the parade, a desire to be first." He requested his congregants put humility first and keep their egos in check.

"There comes a time that the drum major instinct can become destructive," King said. "If it isn't harnessed, you will end up day in and day out trying to deal with your ego problem by boasting."

At its worst, King said, the drum major instinct may lead to elitism and racial prejudice. But, he added, the instinct may be used for good -- for justice, for love, for generosity. It's a belief that's worth taking to heart at the King Memorial, on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, anywhere or anytime.

"If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice." ("Amen," called the congregation.)

"Say that I was a drum major for peace." ("Yes.")

"I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter."

No comments:

Post a Comment