For now, the region is cheering France’s launching of a war on many fronts against the jihadists although it is likely to drag on for many more months

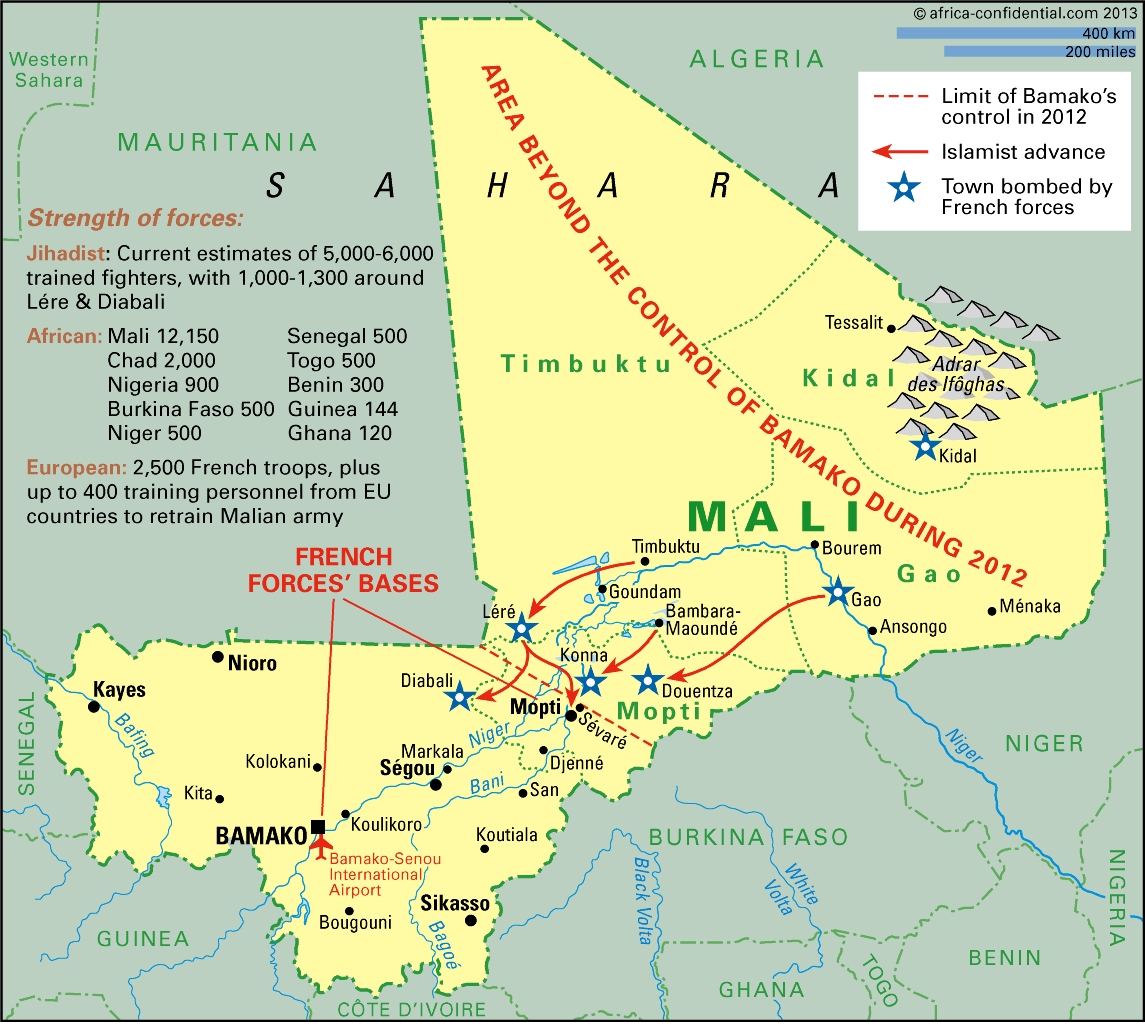

As France pours men and money into the battle against jihadists, the contours of Mali’s crisis are rapidly changing. Bombing raids may have ended the militants’ hegemony over the people of Timbuktu and Gao, but their campaign is far from over. Restoring some security across the Sahara will be a slow and painful business, with many reverses. Pounded by French air strikes near Leré, fighters led by Al Qaida’s Algerian commander Abdel Hamid Abou Zeid quickly hit back, attacking Diabali. Then, half a desert away, on 16 January Moulathmine Islamist militants took 41 foreign oil workers hostage at In Amenas, south-east Algeria.

The timetable for the West African military intervention approved by the United Nations Security Council in December has been accelerated (AC Vol 54 No 1, Talk first, fight later). Yet the effectiveness of this new force remains to be tested. Governments have quickly promised deployments but are slower to deliver them. So has the European mission to retrain Mali’s army, whose fragility is evident. Will contributing countries still want their experts to work alongside Malian troops if they are hurried into combat?

Direct French intervention on 11 January was sparked by the discovery that the jihadist advance into Konna, a town just 56 kilometres north of the key Sévaré military base, the lock on the gateway to Mali’s populous south, was not just a negotiating ploy to gain new concessions. Ansar Eddine, led by the Malian Tuareg Iyad ag Ghali, had recently pulled out of talks with the government and the secular Mouvement national de libération de l’Azawad (MNLA), brokered byBurkina Faso. French surveillance revealed that Ag Ghali’s men had been joined by fighters from Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Mouvement pour l’unicité et le jihad en Afrique de l’ouest (MUJAO) in a two-pronged push to seize Sévaré and the nearby key town of Mopti. Some 200 vehicles, carrying thousands of fighters, were converging on this critical area from Léré and Douentza.

Victory would have left them free to seize Sévaré, whose runway is the only one besides Bamako able to receive large aircraft. Victory would have opened the route to Bamako and critically undermined the international intervention planned for later this year.

France flies to war

That is why, as Malian forces were being overrun, French President François Hollanderesponded to the request for help from Malian President Dioncounda Traoré. He dispatched Burkina-based Special Forces and attack helicopters on 12 January, following up with Mirage and Rafale bombing strikes on Islamist camps and supply bases across the north. A French helicopter pilot and at least ten Malian soldiers were killed. Jihadist casualties were much higher.

That is why, as Malian forces were being overrun, French President François Hollanderesponded to the request for help from Malian President Dioncounda Traoré. He dispatched Burkina-based Special Forces and attack helicopters on 12 January, following up with Mirage and Rafale bombing strikes on Islamist camps and supply bases across the north. A French helicopter pilot and at least ten Malian soldiers were killed. Jihadist casualties were much higher.

Since then, as the militants fought back, the Malian army has shown little capacity to mount counter-attacks, even with air support. So France ratcheted up its engagement, from a few hundred troops to an expected 2,500. Meanwhile, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) pledged over 5,000 soldiers, with the first arriving on 17 January. France is following air attacks by deploying ground troops and armoured vehicles to supplement the small commando teams around Sévaré, Diabali (170 km. north of Ségou) and the key Niger River bridge at Markala.

Following France’s long-range air strikes, most militants have pulled out of Douentza, Timbuktu and Gao. However, they are far from defeated. During months of control, they have hidden weapons and fuel in remote places. They are comfortable operating in desert terrain. Those fighting in the west are, says French Defence Minister Jean-Yves le Drian, determined, well-trained and heavily armed.

The future campaign

President Hollande has said that he will keep French forces in action, not only until ECOWAS troops are ready but until Mali is in a position to restore constitutional democracy and the jihadists have been expelled, killed or captured. It is possible that the intervention forces together with the army could restore control over the main towns relatively quickly but would then face a long campaign to re-establish security at local level.

President Hollande has said that he will keep French forces in action, not only until ECOWAS troops are ready but until Mali is in a position to restore constitutional democracy and the jihadists have been expelled, killed or captured. It is possible that the intervention forces together with the army could restore control over the main towns relatively quickly but would then face a long campaign to re-establish security at local level.

Already, villagers living around Sévaré report that the militants are hiding in the countryside, sometimes posing as civilians. In Konna, they took the town by infiltrating discreetly and then killing local forces. Even five days after the first French assault had forced them to disperse, they still slipped back into town to buy fresh food.

Inter-communal suspicion could also increase as Malians of Bambara, Peul or Songhai ‘black’ ethnicity accuse their ‘white’ Arab and Tuareg compatriots of sympathising with the militants. For months, light-skinned Malians travelling to Bamako from the north have preferred to go through Burkina rather than take their chances at trigger-happy army checkpoints around Sévaré. Songhai villagers have been re-forming the Ganda Isso and Ganda Koy militias; in the past these had poor human rights records.

Power games

Mystery still surrounds Ansar Eddine’s decision to pull out of the Ouagadougou talks and join a major new offensive. There were rumblings that AQIM and MUJAO had put pressure on Ag Ghali to end the negotiations or that Ansar Eddine fighters were defecting to those groups, rich with cash from drug trafficking and hostage ransoms. One senior Ansar Eddine commander is reported to have been killed near Konna. Some reports suggest Ag Ghali fled to his Ifoghas tribe’s heartland around Kidal. There were reports of other conflicts among the jihadists late last year. One commander, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who is widely linked to the In Amenas attack, is reported to have differed with AQIM chiefs Abou Zeid and Yahya Abou el Hamame, and developed ties to MUJAO (AC Vol 53 No 15, The jhadists take over). Meanwhile Omar Ould Hamaha, a Malian Arab (Bérabiche) who had been involved with both Ansar Eddine and MUJAO, has founded a new group, Ansar el Charia, drawn from his own people (AC Vol 53 No 8, Rebel against rebel – against the rest).

Mystery still surrounds Ansar Eddine’s decision to pull out of the Ouagadougou talks and join a major new offensive. There were rumblings that AQIM and MUJAO had put pressure on Ag Ghali to end the negotiations or that Ansar Eddine fighters were defecting to those groups, rich with cash from drug trafficking and hostage ransoms. One senior Ansar Eddine commander is reported to have been killed near Konna. Some reports suggest Ag Ghali fled to his Ifoghas tribe’s heartland around Kidal. There were reports of other conflicts among the jihadists late last year. One commander, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who is widely linked to the In Amenas attack, is reported to have differed with AQIM chiefs Abou Zeid and Yahya Abou el Hamame, and developed ties to MUJAO (AC Vol 53 No 15, The jhadists take over). Meanwhile Omar Ould Hamaha, a Malian Arab (Bérabiche) who had been involved with both Ansar Eddine and MUJAO, has founded a new group, Ansar el Charia, drawn from his own people (AC Vol 53 No 8, Rebel against rebel – against the rest).

The MNLA has offered to support the French campaign, although the group’s strength is much reduced. The Tuareg former Deputy Chief of Staff, Major General Al Haji ag Gamou, commander of semi-regular forces attached to the army but defeated last year, is reported to be planning a pro-government assault on Ménaka, in the far east, from their refuge in Niger (AC Vol 53 No 4, Libyan arms fuel Tuareg revolt & MNLA's deadly mobility). He may have up to 600 men, largely drawn from his Imghad clan.

Bamako fallout

In Bamako, recent events have undercut the putschist leader Captain Amadou Sanogo and rendered irrelevant his long opposition to military intervention. His rhetoric about the determination and capacity of the Malian army now looks ridiculous. His sympathisers in the vocal nationalist and anti-ECOWAS camp, such as Oumar Mariko, are also weakened and the target of bitter attacks in the Bamako press, much of it politically sponsored.

In Bamako, recent events have undercut the putschist leader Captain Amadou Sanogo and rendered irrelevant his long opposition to military intervention. His rhetoric about the determination and capacity of the Malian army now looks ridiculous. His sympathisers in the vocal nationalist and anti-ECOWAS camp, such as Oumar Mariko, are also weakened and the target of bitter attacks in the Bamako press, much of it politically sponsored.

Many in the traditional political class may see the current situation as an opportunity to fight back. Political rivals have been attacking ex-Premier and presidential hopeful Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, and hinting he sympathised with the rebels. So he has hit back with a campaign to raise money for the troops.

For now, France enjoys a warm welcome and ECOWAS may do, too. A lasting trend may be the gradual rebuilding of the presidency’s authority. Transitional head of state Traoré will still need to launch a credible national consultation on the political future. His respected new Premier, Diango Sissoko, has a consensual, unbombastic style that helps improve government credibility.Ousmane Sy, made Presidency Secretary General in September, has restored some coherence to the presidential office.

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment